Lost In Translation: Using Gettext As A Backend For I18n In Rails

Lost in Translation: Using Gettext as a backend for I18n in Rails

Internationalization of Rails applications has always been a daunting task for me. Faced once again with the challenge of internationalizing an entire codebase, I decided to delve deeper into the reasons behind this complexity and explore alternative solutions.

Note: Throughout this article, I will refer to Internationalization——the process of making an application support multiple languages—as I18n. At times, I will use I18n to refer to tools related to Internationalization, but I will make this explicit.

The default setup

I won’t cover the basic configuration of Rails applications for I18n here, as the Rails guides do an excellent job of that. Instead, we will focus on code examples using the default Rails configuration as a basis for discussion.

Rails applications come with I18n support included by default, using the Simple backend; translations for each language are stored in YAML files in the config/locales folder:

# config/locales/en.yml

en:

welcome: Welcome to my new site

To mark a string for translation—in a view template, for instance—you invoke the I18n.t() method or use the t shorthand syntax in templates that include the view helper:

<h1><%= t(:welcome) %></h1>

This method automatically looks up the translation for the current locale using the key welcome. This approach works out of the box and is effective, but this simple example does not reflect the complexity of internationalizing a codebase at scale. As the YAML files grow, the developer experience deteriorates, leading to frustration, increased translation time, and reduced productivity. I’ll explain why, based on my own experience and beliefs.

I18n should be as unobtrusive as possible

One of my core beliefs is that Internationalization should be as unobtrusive as possible to the developer workflow. Lowering the barrier to translating the application keeps developer engagement with I18n high and boosts adoption.

Considering this, the default workflow—which involves:

- Abstracting strings from the code,

- Creating new named keys, and

- Updating and managing YAML files accordingly—

is far from unobtrusive and hampers developer productivity and experience.

Translations should be easy to maintain

In an ideal setup, appropriate tools would handle the extraction of texts marked for translation, prevent duplicates, index them, and remove stale translations.

Gems like i18n-tasks help in this regard. However, they do not prevent duplicates at different keys, which increases the workload for translators.

Better organization of translation files is not the answer

A suggested solution for managing large translation files is to split them into relevant directories and add scoping to the named keys.

Putting translations for all parts of your application in one file per locale could be hard to manage. You can store these files in a hierarchy which makes sense to you.

I don’t believe this is the answer. If anything, it requires more cognitive effort to determine where a translation key should be added.

The file format needs to be machine-readable, not human-readable. Organizing keys is an unnecessary optimization that provides a false sense of productivity enhancement. As stated previously, “I18n should be as unobtrusive as possible”: developers should not have to deal with translation files or know how to format them. Similarly, translators should not have to handle YAML files directly to complete translations. Therefore, how the files are organized is irrelevant as long as both developers and translators agree on the format.

I18n is a production matter, not development

Having translation files checked into version control within the codebase couples I18n with development workflows. In a typical setup, adding new translations requires a new commit to the codebase, peer review, CI, merge, and deployment. I18n should not happen on GitHub; it should be free from developer dependencies.

This is why I18n should be a production matter. Similar to Content Management Systems (CMS), developers should develop and maintain the infrastructure to manage translations, not the translations themselves.

Convinced there has to be a more manageable way of handling I18n in a Rails app, I embarked on a quest for alternatives. Funnily enough, the Rails guides suggested one alternative solution that caught my attention and turned out to be promising.

Enters GetText

GNU GetText is a suite of conventions, tools, programs and libraries aimed at facilitating the internationalization of source code in the GNU project.

One particular section from the GetText manual caught my attention:

GNU gettext is designed to minimize the impact of internationalization on program sources, keeping this impact as small and hardly noticeable as possible. Internationalization has better chances of succeeding if it is very light weighted, or at least, appear to be so, when looking at program sources.

I explained previously how an unobtrusive I18n process would boost adoption and engagement amongst developers. Since the Rails guides mentioned GetText as an alternative backend to the I18n gem, and it aligns with the philosophy of unobtrusive I18n, I decided to learn more about the project and implement GetText paradigms in a Rails application.

Overview of GetText

I won’t delve in too much details about the GNU GetText project. For those interested in learning more about the history of the project and its details, I suggest you take time to review its dedicated page as well as its manual.

Here’s a simplified overview of how GetText works:

- Developers mark strings as translatable in the code. The original string itself is not abstracted from the code and remains there.

- A program parses the strings marked in the previous step and registers them in a

.POTfile, which acts as a template for future language files. - New supported languages are created in

LANG.POfiles from the.POTfile, whereLANGis the two-letter key for the language. (frfor French for instance) - Translators use appropriate editing software to add translations to the newly created

.pofiles. (They can edit them directly but need to respect the format, hence the recommendation for a dedicated software) - As the code evolves, and strings marked as translatable are added/updated/removed, a program updates

.pofiles to reflect those changes.

A simple .po file looks like this:

# locales/fr.po

#: app/views/pages/home.html.erb:4

msgid "Welcome to my new site"

msgstr "Bienvenue sur mon nouveau site"

#: app/views/pages/home.html.erb:8

msgid "Discover our offer below"

msgstr "Découvrez notre offre ci-dessous"

A .po file is a succession of (msgid, mgstr) entries, where msgid is the original untranslated string as seen in the code, and msgstr is the translated string in the target language. Each entry can include comments, providing information about where the string is located in the code, comments from developers and translators, or flags.

Translators can add translations directly to those files or use a PO editor to do it. Those files are the interface between the developers and the translators. The benefit is that code considerations are abstracted away from translators, and translation considerations are abstracted away from the code.

Let’s see how to implement this in a Rails application.

Rails integration of GetText

As mentioned earlier, GetText was originally created as part of the GNU project. An adapted Ruby version of GetText exists and offers similar features to the original GetText:

- Rake tasks for extraction of strings marked as translatable and generation of

.pofiles - Translation helper methods:

_(),n_(),p_()ands_()(we’ll learn about their use below)

However, we won’t be using the GetText gem alone in our sample project. We’ll use a compatible optimized version, faster, extensible and integrated with rails: gettext_i18n_rails, based off fast_gettext.

Here’s our Gemfile:

# Rails integration of fast_gettext

gem "gettext_i18n_rails"

# Required to find translations in the code

gem "gettext", ">=3.0.2", :require => false

Configuration for fast_gettext is added in an initializer. We will define the app domain, the supported locale and the default domain there. Domains are namespaces for your translations, allowing you to separate your app translation from library ones for instance:

# config/initializers/fast_gettext.rb\

FastGettext.add_text_domain "app", :path => "locale", :type => :po

FastGettext.default_available_locales = ["en","fr"]

FastGettext.default_text_domain = "app"

fast_gettext supports multiple backends for the translations, we went for PO files here. As part of the base setup, locale is set through query param in the URL, like ?locale=fr. There’s a helper from the gem to automatically select the correct locale, so we’ll add it to the ApplicationController:

class ApplicationController < ActionController::Base

before_action :set_gettext_locale

end

For alternative mechanism to switch the locale, you can leverage FastGettext.set_locale(locale) to achieve it.

Finally, Here’s our demo template we will work on:

<h1>Welcome to my brand new site!</h1>

<% visitor_count = 1 %>

<p>

Numbers of visitors today: <%= pluralize visitor_count, "visitor" %>

</p>

To keep things simple - it’s an introduction to GetText - I will demo the two main GetText helpers. Bear in mind that GetText has more features, like context-aware translations, text domains and combinations to name a few.

Our app will both be available in English and in French. Let’s add french support for both languages by running the following GetText tasks:

$ LANGUAGE=en rake gettext:add_language

$ LANGUAGE=fr rake gettext:add_language

This will create a locale/ directory at the root of the application folder, a base .pot template file, as a well as locale/fr and locale/en directories containing .po files for the French and English translations.

Now that we are all setup, let’s get a sense of the translation workflow and translate our first texts with GetText!

_() or gettext(): basic translation method

The most basic method for marking a string as translatable is the gettext() method. The _() shorthand syntax is used most of the time. To mark a string as translatable, wrap it inside the method call:

<h1><%= _("Welcome to my brand new site!") %></h1>

<% visitor_count = 1 %>

<p>

<%= _("Numbers of visitors today") %>: <%= pluralize visitor_count, "visitor" %>

</p>

And run the gettext:find task:

$ rake gettext:find

The task will parse the project files for translations. After running the task, the locale/app.pot locale/en/app.po and locale/fr/app.po are updated with two new entries:

msgid "Numbers of visitors today"

msgstr ""

msgid "Welcome to my brand new site!"

msgstr ""

GetText picked up the texts we marked for translations in the msgid and added an empty translation for the msgstr. The string will remain empty in the app.pot file, as it’s the template file, as well as in the en/app.po file since the original strings are already in English and need not be translated. However we will replace the empty strings with their translated version in the fr/app.po` file:

# locale/fr/app.po

msgid "Numbers of visitors today:"

msgstr "Nombre de visiteurs aujourd'hui:"

msgid "Welcome to my brand new site!"

msgstr "Bienvenue sur mon nouveau site!"

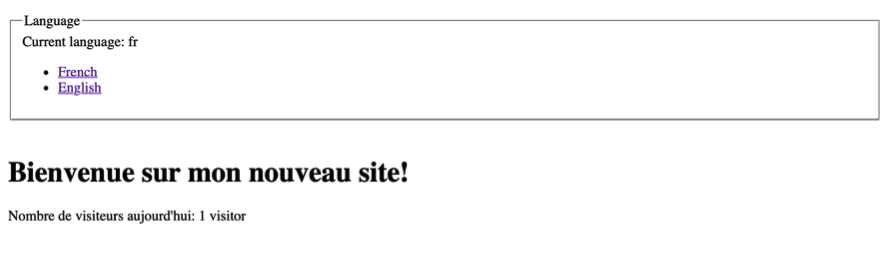

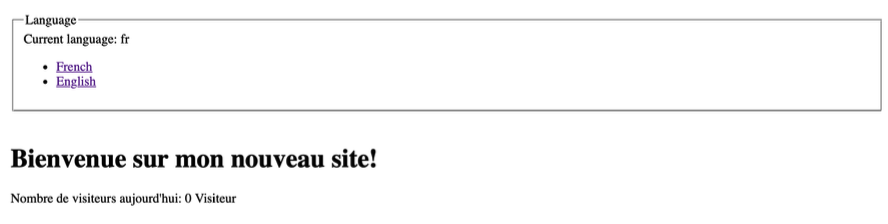

Let’s boot up the server and visit http://localhost:3000?locale=fr:

It works! Both our sentences are translated into French. However we have one remaining item using English, the number of visitors on the site.

n_() or ngettext(): pluralization

GetText handles pluralization with the n_() (shorthand for ngettext()).

Here’s how it works:

n_("Visitor", "Visitors", 1) # => Visitor

Both the singular and plural versions are declared, and an integer is passed as the third argument to decide which one to select. Let’s see how we could use this in our template and run the gettext:find task:

<h1><%= _("Welcome to my brand new site!") %></h1>

<% visitor_count = 1 %>

<p>

<%= _("Numbers of visitors today:") %> <%= n_("%{n} Visitor", "%{n} Visitors", visitor_count) % { n: visitor_count } %>

</p>

$ rake gettext:find

You might have noticed the use of the % operator to format the string returned from n_("...") with the value of the visitor_count initializer. This is needed by GetText to correctly parse the translatable string variables.

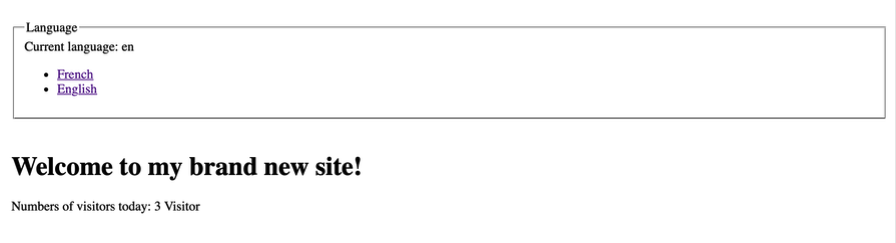

Let’s rerun our server and test it with 3 visitors:

Oops… Looks like it does not work. The reason is that we need to configure the plural forms in GetText. This might seem odd at first, but different languages have different pluralization rules. For instance, the plural form is used with 0 in English. However it’s not the case in French. Configuration for plural forms happens in each app.po file for each language. This is setup in the header of the file as is:

# English

"Plural-Forms: nplurals=2; plural=(n != 1);\n"

# French

"Plural-Forms: nplurals=2; plural=n>1;\n"

nplural relates to the number of plural forms in the languages. English and French have 2 but Polish has 4! plural is a boolean expression to translate the pluralization from the language in code.

Let’s take this occasion to update our French translations:

msgid "%{n} Visitor"

msgid_plural "%{n} Visitors"

msgstr[0] "%{n} Visiteur"

msgstr[1] "%{n} Visiteurs"

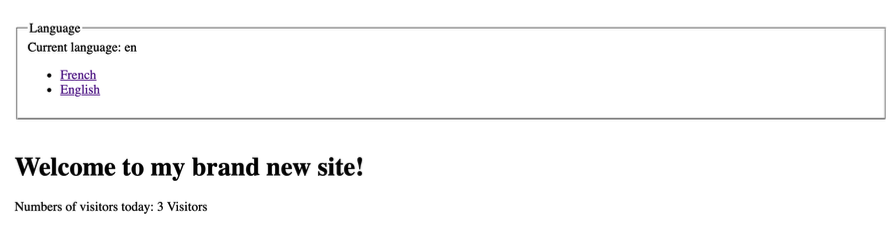

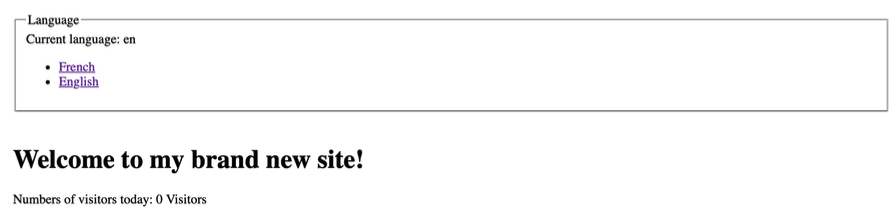

Now that we’ve configured it properly let’s reload our server!

That’s way better. Let’s test our pluralization rules in French and English by setting the number of visitors to zero:

The English version correctly uses the plural form whilst the French version uses the singular form.

And Voilà, we setup our page for translation, using GetText helper methods for translation and pluralization on one hand - a.k.a the developer’s job, and configured and completed the translations in the *.po file - a.k.a the translator’s job.

Final thoughts

Through this simple example, one can see the benefits of using a tool like GetText. Developers are not burdened with translation considerations, such as coming up with key names, organizing translation files, and updating them. All they have to do is mark relevant strings as translatable. The original string remains in the code, maintaining the clarity that named keys would obscure.

Appropriate tooling helps maintain a consistent translation base as the product and code evolve, keeping developers happy and engaged in an important aspect of web application accessibility.

This approach provides translators with their own space to work. They have the relevant context without needing to open a code editor to perform translations.

GetText is a great solution for scaling your I18n infrastructure in a manageable way. However, I am convinced that it can go further. GetText embodies very smart ideas but originates from a time when software distribution and collaboration tools were different. With the setup described above, I a still dependent on the development workflow to have the *.po files edited and validated. Will I use GetText for my current I18n project? Absolutely—there’s no going back to the I18n Simple backend for me. Is this the ultimate answer to I18n? I don’t think so.

But I am eager to learn and work more on the subject!